⚡️ 1-Minute DISCO Download

The core lesson from the famous Lucy v. Zehmer is the objective theory of contracts. In 1954, the Virginia Supreme Court spent months piecing together witness testimony and documentary evidence. Today’s AI tools can complete the same analysis in hours.

💬 Key Quote

The fundamental challenge remains the same as it was in 1954: proving the parties’ true intent through objective evidence. The difference is that today's lawyers have tools that can find that evidence faster, more comprehensively, and more accurately than ever before.

🌊 Dive Deeper

For a detailed look at how modern technology would change the game, jump to the section "Applying Cecilia Q&A to Lucy v. Zehmer." ➡️

We've all made informal agreements. A handshake deal with a neighbor, a promise scribbled on a napkin during dinner, a quick text agreeing to terms. But when does that casual promise become a legally binding contract? And what happens when the stakes are high, the memories are fuzzy, and each party tells a completely different story?

For lawyers, this scenario plays out in courtrooms every day. But perhaps nowhere is this challenge more famously illustrated than in one of contract law's most celebrated cases: Lucy v. Zehmer, where a deal to sell a farm, written on a restaurant check after an evening of drinks, ended up before the Virginia Supreme Court.

The central conflict was deceptively simple yet legally complex: determining serious intent versus a joke. While the court in 1954 had to rely on witness testimony and the "reasonable person" standard, today's lawyers have access to advanced AI tools that can find objective facts and resolve such disputes with unprecedented speed and accuracy.

Let’s take a closer look at this case – and how AI could have solved it in hours rather than months.

What makes a contract? The legal framework

Before diving into our famous case, it's essential to understand what transforms a casual conversation into a legally binding agreement. Contract law rests on several fundamental pillars, but three elements form the foundation of any valid contract.

Elements of a valid contract

Offer

A clear proposal from one party to another. This must demonstrate an intent to be bound by the contract and be definitive enough in its terms that the other party can simply say "yes" and enter into a binding agreement.

Acceptance

Unequivocal agreement to the terms of the offer. The acceptance must match the offer exactly — any changes will constitute a counteroffer.

Consideration

The "what's in it for me?" element. Each party must give something of legal value to the other, whether it's money, services, or even a promise to do (or not do) something.

Two other elements are also key.

Mutual assent

The one that would prove crucial in our case is mutual assent, also known as the "meeting of the minds." Both parties must genuinely understand and agree to the same essential terms of the contract.

And here’s where it becomes tricky. Since courts can't read minds, they use the "objective theory of contracts" to determine whether a binding agreement was formed. This focuses on a subjective understanding manifested objectively through their words and actions.

The key question becomes: Would a reasonable person, looking at all the circumstances, believe both parties intended to create a legally binding contract?

Capacity

This objective standard also requires capacity, the legal ability to enter contracts. Parties must understand what they're agreeing to and not be impaired by factors like intoxication or mental incapacity that would prevent them from comprehending the nature and consequences of their agreement.

A deep dive into the "Bar Napkin" Case (Lucy v. Zehmer, 1954)

The story begins with two acquaintances in rural Virginia who had known each other for years. W.O. Lucy, a local businessman, had long been interested in A.H. Zehmer's Ferguson Farm, a 471-acre property that had been the subject of periodic discussions between the men. Lucy had made inquiries about purchasing the farm on multiple occasions over several years, establishing a pattern of genuine interest.

On the evening of December 20, 1952, Lucy arrived at Zehmer's restaurant in Dinwiddie County with a specific purpose: to make a serious offer. As the evening progressed and drinks were consumed, Lucy made his move. He offered $50,000 for the Ferguson Farm, more than double a previous offer of $20,000.

That caught Zehmer’s attention — he had originally bought the farm for $11,000, and its tax assessment value was $6,300. But his response suggested skepticism about Lucy's seriousness. Rather than immediately accepting or rejecting the proposal, Zehmer engaged in detailed negotiations about the terms. The conversation evolved to include specific elements: the exact acreage, what personal property would be included, and how the title transfer would be handled.

What happened next became the crux of the legal dispute.

The contract

Whether as a test of Lucy's seriousness, a response to the attractive price, or some combination of both, Zehmer took out a pen and wrote the terms on the back of a restaurant receipt:

"I hereby agree to sell to W.O. Lucy the Ferguson Farm complete for $50,000.00, title satisfactory to buyer."

Lucy asked him to make it legally binding by saying “we.” So Zehmer rewrote the terms:

"We hereby agree to sell to W.O. Lucy the Ferguson Farm complete for $50,000.00, title satisfactory to buyer." Both A.H. and his wife, Ida, signed the document.

After the signing was complete, Lucy offered to pay $5 on the spot as earnest money to bind the agreement. When Zehmer declined, Lucy stated that he would return the next day with the full amount.

The pivot

As promised, Lucy returned the next day with his brother and financing arrangements, demonstrating his intent to complete the $50,000 purchase. Only then did the Zehmers refuse to proceed, with A.H. claiming the entire transaction had been a joke, that he'd been too intoxicated to form serious intent and had never believed Lucy was making a genuine offer.

Lucy maintained that, regardless of Zehmer’s belief or disbelief, the detailed negotiations, substantial offer, written agreement, and dual signatures constituted a binding contract.

The case would ultimately turn on a fundamental question: When parties engage in apparently serious negotiations and create written documentation thereof, at what point does the law treat their conduct as legally binding?

The legal battle

Zehmer's defense: "I was joking," "I was drunk," "I didn't really mean it." Zehmer claimed he had been "high as a Georgia pine" and was merely bluffing to see if Lucy actually had $50,000. He insisted the entire transaction was done in jest, with no serious intent to sell.

Lucy's argument: "I believed it was a real offer, and your actions supported that belief." Lucy pointed to several objective indicators of serious intent: the detailed discussion about what "complete" meant (including cattle on the property), the careful rewriting of the agreement to change "I" to "We" so Mrs. Zehmer could sign, and Zehmer's businesslike handling of the transaction.

Note: It can take weeks or even months to uncover the truth through manual discovery processes. Learn how to use generative AI for for quicker, more accurate fact analysis and investigation.

The court's decision

Initially, the trial court sided with the Zehmers. The lower court found that the agreement had indeed been made in jest and that A.H. Zehmer's intoxication prevented him from forming the serious intent necessary for a binding contract.

This ruling seemed to validate the Zehmers' position that no reasonable person would have believed the restaurant receipt represented a genuine business transaction.

However, Lucy appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court, which ultimately reversed this decision and established one of the most important precedents in American contract law.

The court applied the objective theory of contracts, explaining that a contract is formed based on the outward objective actions and expressions of the parties involved, rather than their unexpressed, internal, or subjective intentions. Essentially, would a reasonable person, observing the interaction, conclude that the parties intended to enter into a binding agreement?

The court found that the objective evidence — the detailed discussion, the rewriting of the agreement, obtaining Mrs. Zehmer's signature, and the formal language used in the contract — demonstrated serious intent to a reasonable person, regardless of Zehmer's internal subjective thoughts.

As the court stated: "The law imputes to a person an intention corresponding to the reasonable meaning of his words and acts."

This became a cornerstone case for understanding mutual assent: courts judge intent by external manifestations, not private thoughts. The ruling also clarified specific performance as a remedy, where courts can order a party to fulfill the terms of a contract rather than just awarding monetary damages where that would not be adequate.

The modern solution: Enter artificial intelligence

For decades, lawyers have analyzed cases like Lucy v. Zehmer using traditional methods — depositions, witness interviews, and manual document review. But what if Lucy's lawyer had access to 21st-century technology?

Legal technology isn't about replacing lawyers with robots. Instead, AI-powered ediscovery represents a fundamental shift in how legal teams can analyze evidence and build cases. At the heart of this transformation is generative AI: technology that can understand context, synthesize information, and provide human-readable explanations of complex data patterns.

Related reading: What the Past Two Years of GenAI Mean for Legal’s Future 🤖

Introducing DISCO's generative AI toolset: Cecilia

Take it from me, Cecilia represents the cutting edge of legal AI – a powerful AI partner that handles time-intensive research and analysis tasks that once required weeks of manual effort, and enables legal teams to focus on strategy, advocacy, and client counsel while ensuring no critical evidence goes unnoticed.

You can read about the full Cecilia suite here. For this exercise, I’m going to focus on two core capabilities:

Cecilia Q&A

A generative AI tool that lives in your ediscovery database. It allows you to ask natural-language questions about your case documents and receive answers based only on the information within the database, with citations to the underlying sources that can be quickly referenced or tagged for additional analysis.

Think of it as an incredibly sophisticated law clerk who has read every document in your case and can instantly recall any details, cross-reference information, and explain connections between seemingly unrelated pieces of evidence.

Cecilia Timelines

This tool creates a collaborative timeline in minutes from any pleading or summary document that can be easily updated throughout the life of the case – exactly the type of chronological analysis that won Lucy v. Zehmer.

Together, these tools could transform the months of manual analysis the original case required into hours of AI-powered investigation.

Applying Cecilia Q&A to Lucy v. Zehmer

The power of AI analysis

The transformative power of Cecilia Q&A lies not just in speed but in its ability to synthesize information across multiple sources instantly. In the “Bar Napkin” case, this would have meant:

- Cross-referencing witness statements to identify contradictions

- Tracking timeline inconsistencies in Zehmer's "joke" defense

- Analyzing behavioral patterns that indicated serious business intent

- Surfacing objective evidence that supported Lucy's position

Imagine all the evidence from the Lucy case — depositions, witness statements, correspondence, even records of prior negotiations — digitized and loaded into DISCO. Here are some examples of questions the attorneys could have asked Cecilia Q&A:

- "Is there evidence that Lucy previously tried to buy the Ferguson farm?

- “Is there ample evidence to support their contention that the writing sought to be enforced was prepared as a bluff or dare?”

- "What was Zehmer’s state of mind the night the contract was signed?”

- "What did Mrs. Zehmer say about her husband's state of mind that night?"

- "Did Zehmer ever state that he was joking before Lucy left the restaurant?"

Every answer comes with specific citations to source documents in the case, creating a clear trail from conclusion to evidence, essential for courtroom defensibility.

Using Timelines to Expose the Truth

Generative AI can assist with creating powerful timelines that help legal teams spot patterns and inconsistencies that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Building the Lucy v. Zehmer Timeline

A DISCO-generated timeline from the complaint in the case would reveal compelling insights, such as:

December 20, 1952

W. O. Lucy visits Zehmer's restaurant in Dinwiddie County in the evening.

December 20, 1952

The parties wrote up a contract signed by the Defendant saying they would give up the land for $50,000. Plaintiff offered $5 to ensure the bargain was binding and the Defendant refused.

December 21, 1952

Lucy contacts his brother, J. C. Lucy, and arranges for him to take a half interest in the purchase and pay half of the consideration.

December 21, 1952

There is a social gathering in McKenney where news of the sale circulates. Mrs. Zehmer comments that Lucy got a bargain, and Zehmer tells Lucy he doesn’t want to “stick” him to the deal if Lucy was too intoxicated, to which Lucy insists he intends to go through with the purchase.

December 22, 1952

Lucy hires a lawyer to examine the title to the Ferguson Farm.

December 31, 1952

Lucy’s attorney reports favorably on the title’s status in the title report.

January 2, 1953

Lucy writes to Zehmer stating the title is satisfactory and he is ready to pay the purchase price in cash, and asking when Zehmer will be ready to close the deal.

January 13, 1953

Zehmer responds by letter, asserting that he never intended to sell the farm and that the agreement was made in jest.

The timeline reveals the truth

This chronological layout makes Zehmer's "joke" defense look increasingly implausible. The timeline shows a clear pattern: Zehmer's actions after signing were consistent with a real transaction, and his "joke" claim emerged only when Lucy returned with the money to complete the purchase.

Learn more: How to Build Fact-Based Legal Timelines 🧠

Bonus: DISCO’s other GenAI tools vs. the Bar Napkin Case

I’ll be honest – this blog has been a really fun exercise. Though my argument above demonstrates how Cecilia Q&A and Timelines could have resolved Lucy v. Zehmer in hours rather than months, I took a spin through how DISCO’s other GenAI tools could be used to bring efficiency, expediency, and more thorough review to this case:

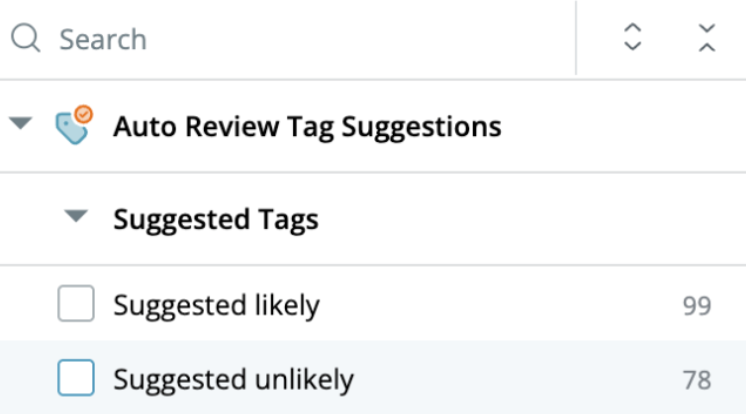

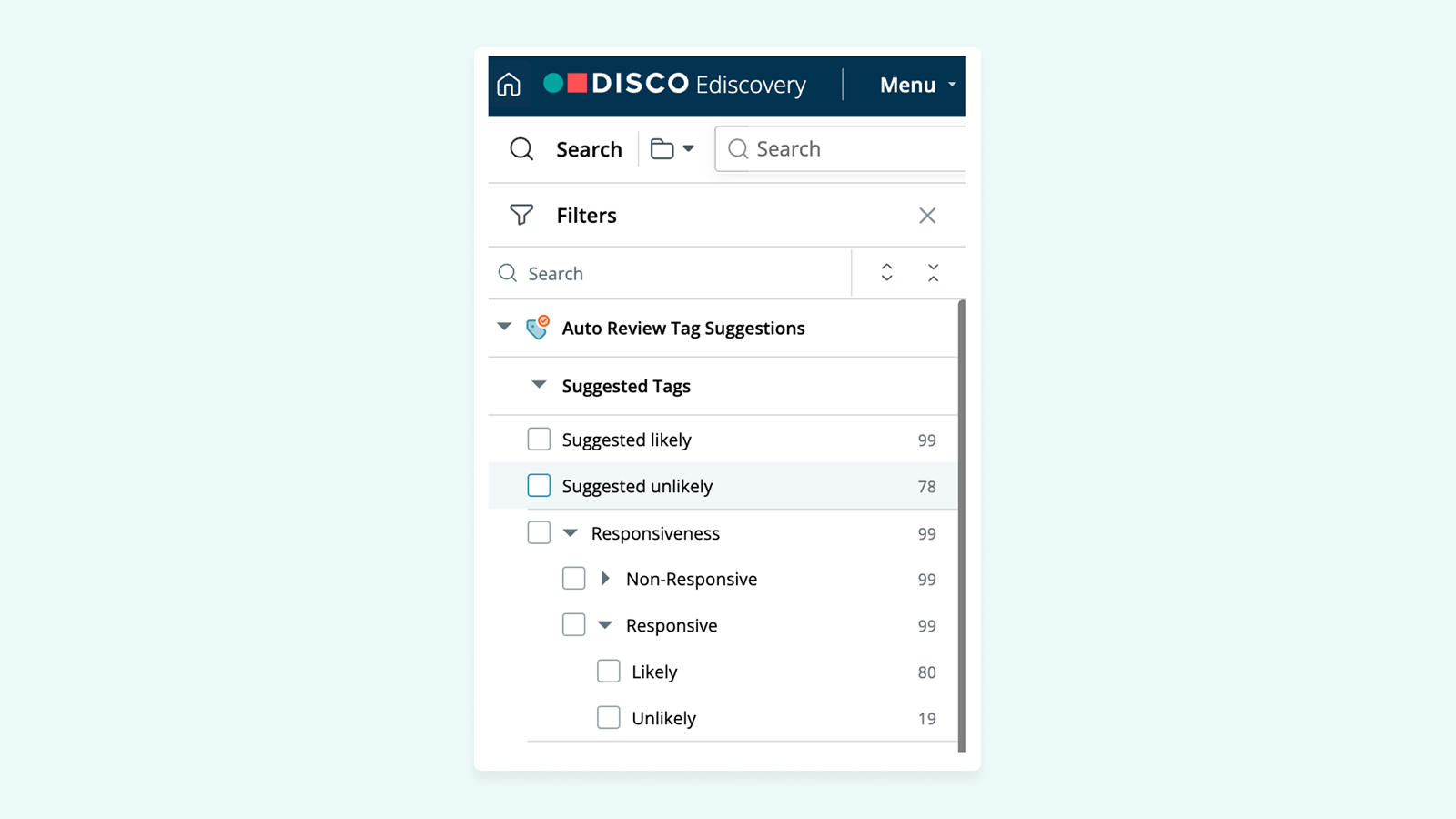

Auto Review – This generative AI tool performs first-pass issue and responsiveness review. It evaluates documents based on tag descriptions, suggests tags, and explains its suggestions, mimicking human review but with greater efficiency and accuracy. Each tagging suggestion comes with a natural-language explanation (e.g.,tagged as Intent Evidence because “this document shows prior discussions as to the purchase of the Ferguson Farm”).

Cecilia Doc Summaries – For lengthy contracts, complex business records, or deposition transcripts, this generative AI tool can generate concise summaries. For example, rather than read a 200-page deposition transcript, you can get a summary along the lines of: “[witness] testified that Zehmer appeared alert during negotiations, discussed property boundaries in detail, and did not appear intoxicated.”

Cecilia Single Doc Q&A - This tool allows you to ask natural-language questions of a single document – so not only can you get a summary of that document, but you could ask, “Did [witness] mention knowledge of Zehmer’s state of mind on the night the agreement was signed?”

Cecilia Deposition Summaries – This tool automatically extracts key testimony from witness depositions, organizing statements both in order they were mentioned in the deposition and grouped by topic. For Lucy v. Zehmer, it might create topic summaries such as "Zehmer's Sobriety," or "Previous discussions surrounding purchase of the Ferguson Farm," including an AI-generated summary of each topic along with links to the citations in the transcript.

Conclusion: AI can create certainty in an uncertain world

The journey from the classic Lucy v. Zehmer case to today's AI-powered legal tools illustrates a fundamental evolution in how lawyers prove intent and build cases. The objective theory of contracts has always required lawyers to find evidence of intent through external actions and statements. What's changed is how we can now find and analyze that evidence much quicker and more efficiently.

In 1954, the Virginia Supreme Court spent months piecing together witness testimony and documentary evidence to determine whether a reasonable person would believe Zehmer was serious. Today, with tools like Cecilia Q&A and Cecilia Timelines, that same analysis could be completed in hours, with greater accuracy and a more comprehensive evidence review.

The stakes in modern litigation continue to rise, and the volume of discoverable information grows exponentially. Text messages, emails, Slack conversations, financial records, and social media posts create vast digital trails that can either support or undermine claims about intent, knowledge, and good faith. Imagine if Lucy or Zehmer had an Instagram account back then!

Whether it's a handshake deal gone wrong, a complex M&A dispute, or employment contract litigation, the fundamental challenge remains the same as it was in 1954: proving the parties’ true intent through objective evidence. The difference is that today's lawyers have tools that can find that evidence faster, more comprehensively, and more accurately than ever before.

As we move forward in an increasingly digital world, the partnership between legal expertise and AI technology offers unprecedented opportunities to deliver justice more efficiently and effectively. The "bar napkin" case may be 70 years old, but its lessons about offer, acceptance, intent, and the search for truth remain as relevant as ever — we just have better tools to find the answers.

Schedule a demo with DISCO to learn how we can help you, using applied analytics and AI, better case assessment, and optimized cost and performance.

.webp)

%20(1).jpeg)